Improving Public Health Screening With Technology

It seems like we’re collecting and analysing data on every step of our way. The biggest opportunity for public health screening programs lies in wide-spread data collection and analysis.

This issue presents how technology could become more invested in screening and improve how it's carried out. It’s not that the current way is not effective or beneficial. It’s just about making it even better. While researching, this topic proved to be very complex and multi-layered, which is exactly what made it interesting.

The World Health Organization defines screening as “the presumptive identification of an unrecognised disease or defect by the application of tests, examinations, or other procedures which can be applied rapidly. Screening tests sort out apparently well persons who probably have a disease from those who probably do not. A screening test is not intended to be diagnostic”. Since its adoption, it has significantly improved the population’s health.

Data

It seems like we’re collecting and analysing data on every step of our way. The biggest opportunity for public health screening programs lies in wide-spread data collection and analysis. This doesn’t mean to just collect health data about individuals, but about populations and where and how they live.

In the past, one of the biggest public health challenges was access to clean water, which was closely related to the occurrence of cholera. The susceptibility of the individual to cholera was determined by where they lived. The key part was this piece of information. These days, it’s the same. Just that access to clean water in developed countries is generally not a problem anymore.

But air pollution is, which is an indicator of diseases such as asthma, lung cancer and COPD. Connecting this to population clusters and using it to enrol them in specific public health screening programs presents an opportunity for improving the population’s health.

This is very much looking at the risk-factors from the population’s stand-point. Improving the quality of life for a population by reducing the amount of sugar in foods, promoting a healthy lifestyle (even through wearables) is easier than focusing on each individual.

New streams of data on issues such as air pollution, accessibility of green spaces, data from across government services, and acute problems such as drug use or changes in the labour market are becoming easier to collect at scale, and could all be useful. - The Health Foundation

A similar principle can be applied to screening for chronic diseases in a population, but it can’t be too wide-spread. Some studies show that a population-wide mammography screening in China can do more harm than good. The key here is collection, analysis and proper use of data.

On the other side, connecting data to specific individuals has its benefits and drawbacks. On one hand, it’s a step towards personalised medicine and treatment, which also makes way for personalised screening programs. However, the cost-to-benefit ratio in such a wide-spread, but very individual-based approaches is very high.

Adoption of Technology

Collecting data can be very specific. The adoption of wearables is massive and smartphones are in everyone’s pocket. At first, this sounds great and beneficial. On the other hand, this excludes older people, at least for now. It also deepens the gap in access to healthcare, where the healthy get healthier and the unhealthy get unhealthier. Kind of like “the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer” idea.

But among all that data and possible applications, every intervention might become too reductionist by focusing on a very specific issue and forgetting about the bigger picture.

Take genetic profiling for example. It sounds great to have the chance of almost predicting future chronic illnesses. But on the other hand, focusing too much on those might cause us to miss the rest. For example, heart disease is strongly related to our lifestyle (but also has a genetic component) and undue stress because of knowing about the predisposition.

This sounds contrarian to precision medicine, but it’s not. It’s very much supporting it since every individual (and the whole population for that matter) has to consider the person as a whole. Not just a bunch of cells and genes put together.

Examples

“Moving services to digital channels could expand access to care, reduce the stigma of accessing them, or help people fit them in around work and family commitments.” The risk is once again digital exclusion, but there are still some very interesting approaches to screening that smartphones and wearables offer us.

A few issues ago, I wrote about a digital biomarker for diabetes, which means using your smartwatch or smartphone’s camera for detecting changes in the vascular bed. This is probably one of the best ways to screen for diabetes, other than performing regular blood glucose measurements. Which is also possible using CGMs, but is less convenient.

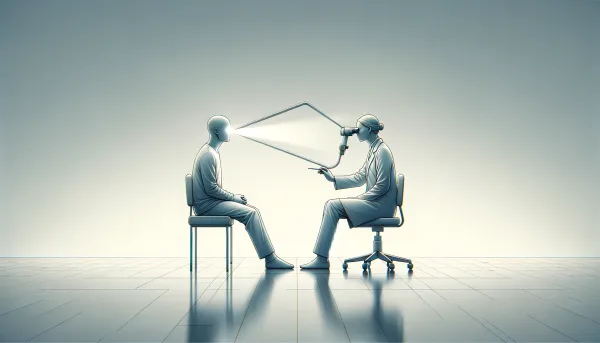

It’s even possible to use technology to screen for diabetic retinopathy. We still need an ophthalmologist to do that, but a recent study published in Nature Eye clinically validated an AI-based screening tool.

A similar system is also developed to be used in detecting Parkinson’s with a smartphone and AI. The system analyses the images of the fundus of the eye and recognises “smaller-than-usual blood vessels in the affected patients’ retinas.” The principle behind this that specific markers in the eyes indicate changes in brain physiology. All you need is a smartphone and a special lens. Much simpler and less expensive than a CT or MRI scan.

Another neurological condition that’s also crucial to detect early is Alzheimer’s disease. I wrote about this in issue #37 and an app called Mindset4Dementia (I’m a huge fan) uses answers to questions from the general population and teaches an AI how the brain works. This is then used to screen for Alzheimer’s disease in the more vulnerable part of the population.

Even IBM is developing an AI-based diagnosing tool for Alzheimer’s based on hand-writing that has a 75% accuracy. Again, an elementary principle that has huge implications in public health.

Tackling Underlying Causes

No matter how much we discuss screening and prevention, tackling the underlying cause is the way to go. If the air is polluted, strive to make it cleaner. If people don’t move enough, build more parks. And most importantly, teach people how to prevent the most common chronic conditions and encourage them to take care of their health.

If technology doesn’t help 100% in screening it can at least do so in providing information and feedback.